Continental Drift? India-Russia Ties After One Year of War in Ukraine / Akriti Kalyankar, Dante Schulz

By Akriti (Vasudeva) Kalyankar • Dante Schulz

In South Asia

“What we realized in the last couple of years, based maybe on a direct fallout of the Russia-Ukraine conflict and the pandemic situation…[was] that we need to become self-reliant. We also need to have more robust and secure supply chains […] to better handle security challenges as we move forward.”

— General Manoj Pande, Indian Chief of Army Staff, January 14, 2023

Over the past year, domestic and international observers have questioned India’s position on the Russia-Ukraine war, often reading its muted public stance as support for Russia. But as the words from General Pande above suggest, a closer look at recent Indian policy reveals quiet but significant steps to reduce New Delhi’s dependence on Moscow. Russia’s poor performance in the war, its constrained ability to produce arms post-Western sanctions, and its global isolation have forced a debate within the Indian strategic establishment about the future utility of Russia as a strategic partner.

India has long seen Russia as a reliable partner that has supported it at the United Nations (UN), played an integral role in building up Indian military capabilities across domains, and allowed it the space to practice strategic autonomy vis-à-vis the West. Post-invasion, however, New Delhi faces a host of challenges linked to its ties to Moscow. Domestically, the war has raised concerns about food, fuel, and fertilizer insecurity. Internationally, India has had to balance its support for the principle of territorial sovereignty and integrity with a hesitancy to vote against Russia at the UN. The war has also turned India’s primarily Soviet/Russian-origin military equipment into a liability due to concerns over battlefield performance and availability challenges.

In response to these concerns, policymakers in Delhi have sought to walk a tightrope in staking out a middle ground publicly while accelerating three significant, long-term shifts:

- A greater focus on defense diversification and indigenization;

- Growing caution over risks from China-Russia ties; and

- Deepening partnerships with like-minded Western partners, like the United States, France, Israel, and multilateral groupings.

Towards Self-Reliance in Defense

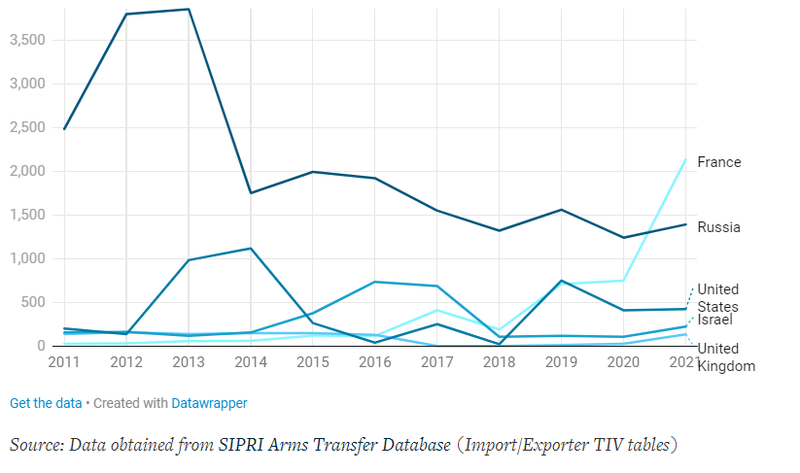

To be sure, India’s twin strategy of diversifying its military equipment sourcing while also focusing on defense indigenization predates the war. As Figure 1 suggests, Russian defense supplies to India have declined over the past few years as those from Western partners like France have risen. Additionally, in the 2022-2023 budget, the Indian government allocated about 68 percent of the capital procurement budget to the domestic defense industry compared to 58 percent the previous year.

Some of these efforts have started to bear fruit recently. For instance, in April 2022, India successfully tested its first fully domestically designed and produced loitering munitions. In February of this year, the domestically designed and produced HAL Tejas fighter undertook its maiden landing and takeoff from India’s first indigenously-produced aircraft carrier, the INS Vikrant.

FIGURE 1 – INDIA’S ARMS IMPORTS FROM MAJOR DEFENSE PARTNERS, 2011-2021

Value of India's Arms Imports

(Trend Indicator Values In USD Millions)

The war has only further underlined the vulnerabilities of relying on Moscow for key defense supplies. For example, Gen. Pande specifically pointed to India facing sustenance issues and concerns regarding timely delivery of spare parts and military equipment in the wake of the Russia-Ukraine war and sanctions imposed on Moscow. Most worryingly for Delhi, the war has delayed the delivery of prized S-400 air defense systems. Fears over Russia's ability to deliver big-ticket items in the future may also explain India's decision to suspend some arms deals with Moscow. In addition, about two months after the war began, Indian Defense Minister Rajnath Singh added 101 items, many of which were previously sourced from Russia, to a growing list of defense equipment that will now be produced indigenously.

Fears of a Russia-China Strategic Embrace

The war in Ukraine has likewise raised difficult questions in New Delhi about implications of the deepening Russia-China alliance. While their announcement of a “no limits” partnership preceded the war, the past year has only solidified Russia-China ties and brought into stark relief an outcome Delhi has been actively working to thwart: Moscow becoming more dependent on Beijing. Delhi has traditionally pursued a wedge strategy vis a vis Russia and China, seeking to incentivize Moscow’s neutrality in an India-China standoff while securing its own immediate defense needs. India’s purchase of the S-400 air defense system, its participation in the Russia-India-China trilateral, and its economic investments in Russia’s Far East reflect this approach.

However, in the wake of the Ukraine war, many Indian analysts rightly observe that this strategy may have outlived its utility. Instead, they argue that India must prepare for a weakened Russia that is more beholden to China and could be pushed to take actions inimical to India’s interests, such as holding back emergency defense articles. There is historical precedent for this: the Soviet Union delayed delivery of the Mig-21 aircraft to India to ensure support from China during the Cuban missile crisis. More importantly, Indian defense planners must contend with the national security implications of Chinese components potentially making their way into the Indian arsenal via Russian weapons in the future due to sanctions on Moscow and its lack of other suppliers.

The Indian debate on whether it still possesses meaningful mechanisms of influence over Moscow to prevent a Russian drift toward China has still not been resolved. Indeed, India has a degree of economic leverage over Russia, as one of its few remaining non-China economic partners. Delhi’s purchase of discounted crude oil from Moscow could arguably be seen in this light. From April to December 2022 alone, India imported $21.7 billion in Russian crude oil—17.1% of its total crude imports—compared to about 0.94 billion in 2020-2021 or 0.2% of total crude imports. This theoretically gives Delhi levers to use vis-à-vis Moscow if Russia acts against Indian interests at the behest of China.

Jaiya Lalla contributed research. Photo: Alexander Demianchuk.

Read in full at source